Exposition in Dialogue

You can deliver exposition via dialogue, but you have to finesse it a little. Here we discuss how you can disguise exposition so it doesn’t feel contrived.

Subjective Conflict

The idea behind subjective conflict is this: the reader can sometimes experience conflict even when the characters in the story don’t. This week’s article appears at DIYMFA.

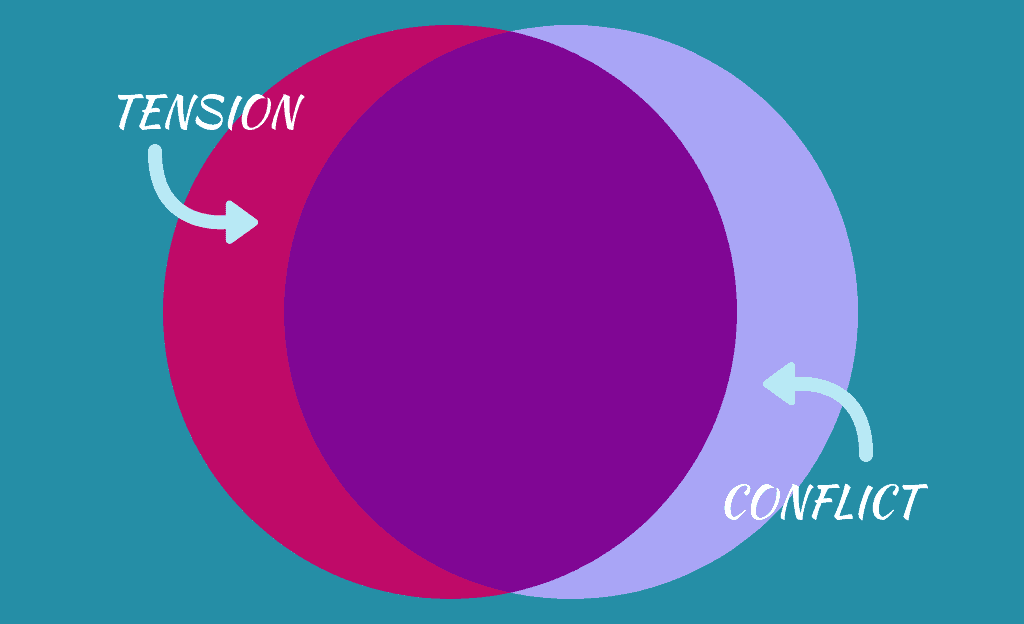

Why Your Story’s Conflict May Fail to Grip Readers

Is your story’s conflict gripping readers? Not all conflict is created equal. Some creates tension; some doesn’t. And in fact, conflict isn’t the only way to create tension.

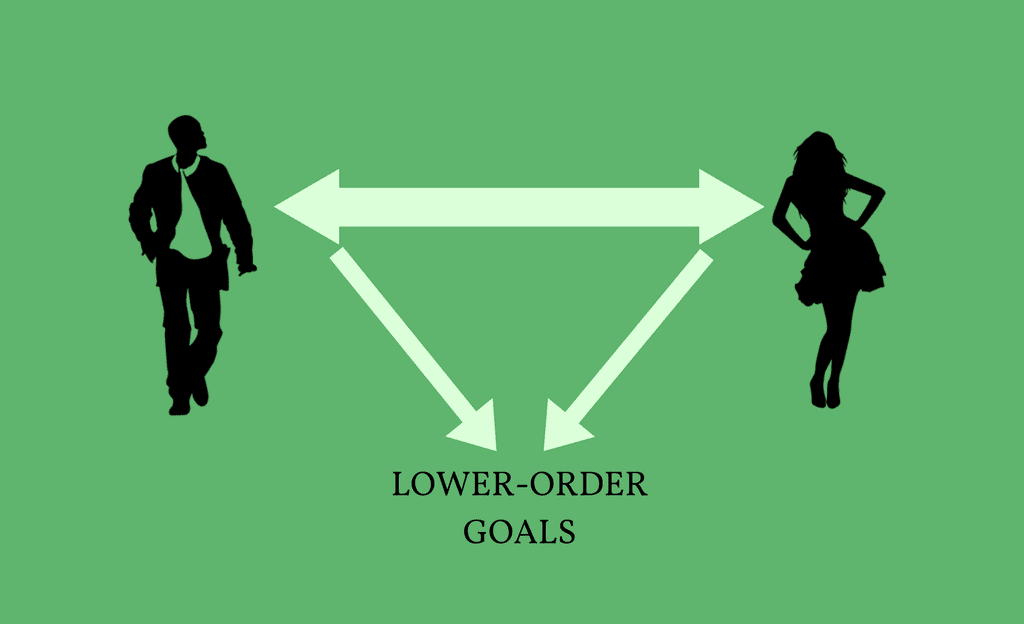

Triangulate Dialogue

To avoid flat dialogue scenes, learn to triangulate the characters’ interaction with a lower-order goal.

Escalating Complications

“Escalating complications” is my preferred term for what’s commonly known as “rising action.” What is rising action? And how can you use it to maintain reader engagement in the middles of your scenes and stories? We take a lesson from iguanas and snakes here.

Why You Need Strong Antagonists in Your Story

Let’s get something straight right off the bat: Your story is about your protagonist. That is, the protagonist is the star. By definition. Even if you have a very engaging and sympathetic antagonist, the reader identifies more with your protagonist’s struggle and desire. If that’s not the case, you have the wrong protagonist.

That’s the first thing to keep in mind when dreaming up and/or depicting your antagonist: the protagonist is the star of the show. The antagonist’s purpose is to serve the author’s goals for the protagonist.

Two Conflicts: Problems vs. Obstacles

We’ve all heard about the importance of conflict in storytelling. One of my favorite quotes in this regard comes from Charles Baxter, who says, “Only Hell is interesting.” If there’s not trouble in the story, we don’t want to hear about it. That’s not to say we want trouble to win out. On the contrary, when a story has elements of conflict or trouble, they work to expose what’s good and right and true about the protagonists with whom we empathize and sympathize.

But I want to unpack conflict a touch more because it comes in a few different varieties.