Two Conflicts: Problems vs. Obstacles

We’ve all heard about the importance of conflict in storytelling. One of my favorite quotes in this regard comes from Charles Baxter, who says, “Only Hell is interesting.” If there’s not trouble in the story, we don’t want to hear about it. That’s not to say we want trouble to win out. On the contrary, when a story has elements of conflict or trouble, they work to expose what’s good and right and true about the protagonists with whom we empathize and sympathize.

But I want to unpack conflict a touch more because it comes in a few different varieties.

Action vs. Information: Convey Info without Stalling the Story

Information conveys states of mind, states of existence, but not states of affairs (unless you’re dramatizing the past via a flashback, but that’s not conveying the present-time story state of affairs). But if your information (facts, past, interiority, context) is not relevant to the story’s state of affairs, your reader is going to tune it out—or worse, come to distrust your narration.

Juggle External Action and Interiority

External refers to what’s happening outside of characters’ minds. It’s the stuff that an observer could see. You could film it pretty easily. Internal refers to what’s going on inside a character’s head: feelings and thoughts. Prose storytelling regularly informs us of characters’ interiority in ways that, say, a screenplay cannot.

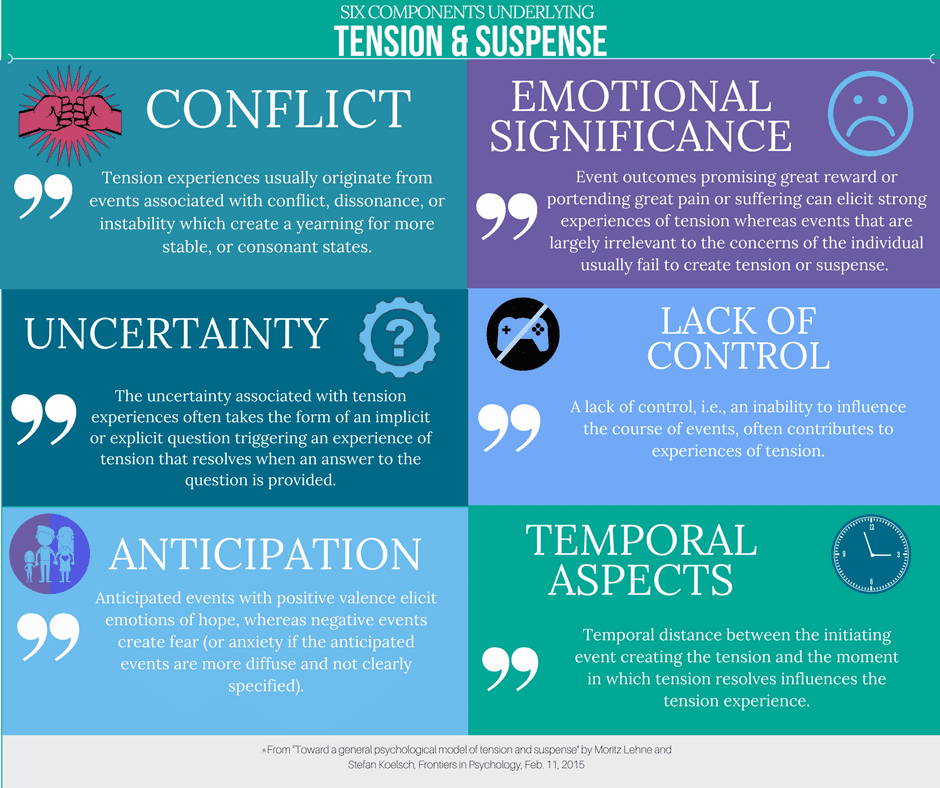

Creating Suspense

I recently came across this insightful analysis of suspense in the opening of the film Inglorious Basterds. In it, there’s a mention of an article from the Psychology journal, Frontiers in Psychology about Tension and Suspense. The authors, Moritz Lehne and Stefan Koelsch, posit six components underlying suspense and tension, which I find useful in thinking about crafting scenes to engage your readers and get your characters into trouble.

Time Digressions in Narration

So, first of all, it’s worth noting that most of the story’s momentum comes from the “What’s going to happen next?” question, and that’s a question that arises from present-time story. Most of the story’s meaning, however, arises from the time digressions.

Common Problems in Manuscripts

I work with a lot of manuscripts–everything from novels to short stories; chapters, scenes; essays, memoir–and in this video, I go over four of the most common problems I’ve encountered in the work I’ve read in the past year or so.

Scene vs. Summary

I introduced this concept of scenes vs. summary in my post on the four ways to break down page-level craft. Here, in more detail, is what scene vs. summary is all about. And I’ve included some explanation on how the story writer can benefit from knowing this aspect of craft.

Page-level Storytelling: Four Ways to Break Down Your Narration

When you’re putting together scenes in your story, you’re not just writing a list of events. Your narration guides the reader by providing more than present-time action. Consider these four breakdowns to help you craft your scenes.

Story Consumption: How to Read Like a Writer

In my MFA program, we were required to read 80 books over the two-year course of study. Like most writers, I was already a voracious reader, but time constraints and job demands had meant that I read far fewer than 40 books a year. In reading such a large volume of books, though, I came to embrace some tenets of story consumption: