Verisimilitude: What it is and how it works

Verisimilitude all about getting the reader to suspend disbelief and see realistic depictions of character, setting, and events. But what does it mean for such story elements to be realistic?

Delight: The Secondary Source of Reader Engagement

Though tension is maybe the main source or reader engagement, there are several sources of “delight” that help charm the reader and make books memorable.

Dramatic Prognosis: a tool for designing strong plots and improving weak ones

The dramatic prognosis is the calculation the audience makes about the hero’s chances of reaching the goal. You can examine the dramatic prognosis within your story in the planning stage or in the revision stage; it may be helpful in highlighting where the story is lacking.

What Does the Inciting Incident Actually Do?

The inciting incident is often misunderstood. Even seasoned writers sometimes make claims that there can be multiple inciting incidents or that it can occur before the story even begins. But I would argue that most of those claims are rooted in a misunderstanding of the role the inciting incident plays within a story.

Turning Points Propel Your Story

Turning points are why scenes exist. So it’s essential to understand how and why they work within your story to propel both plot and character.

The Case for Pantsing

Writing “by the seat of your pants,” aka “discovery writing” works better for some writers than outlining does. Read about the rationale for pantsing here.

Subjective Conflict

The idea behind subjective conflict is this: the reader can sometimes experience conflict even when the characters in the story don’t. This week’s article appears at DIYMFA.

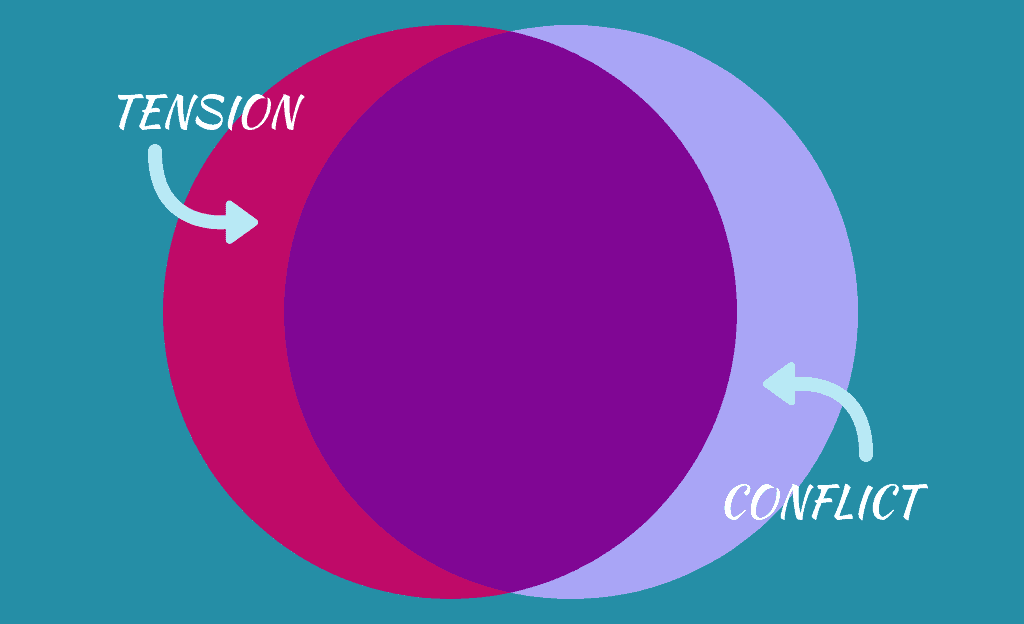

Why Your Story’s Conflict May Fail to Grip Readers

Is your story’s conflict gripping readers? Not all conflict is created equal. Some creates tension; some doesn’t. And in fact, conflict isn’t the only way to create tension.

Use “Urgent Story Questions” to Create Tension

Sometimes, the main source of tension in a story comes from a lingereing “urgent story question” that nags at the reader. You should be conscious of your story’s USQs so that you can make the most of them and create a more gripping story.

The Problem with “Show, Don’t Tell”

The old writing adage of “show, don’t tell” is good advice, but it can occasionally get writers in trouble. Good writers sometimes fall prey to hyperdetailing–giving excessive description without serving the story.