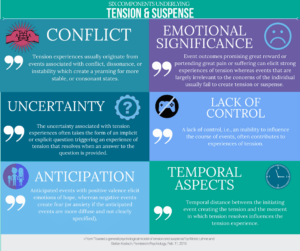

Let’s talk reader engagement. It comes from tension and from the reader’s anticipation of change. And there are three situations a writer can create in order to cultivate dramatic tension and to get readers anticipating change: mystery, suspense, and dramatic irony.

These labels name “story/audience relationships,” notes Robert McKee in his book Story.

In this brief article, I want to introduce these concepts and give some clear examples for each.

Mystery

When the audience knows less than the characters do, we have a “mystery” situation. What does this look like? Pick up any book you have lying around, and the read the first page. You’re bound to see some mystery. Here are the first few lines of David Mitchell’s Slade House, the first book I grabbed:

Whatever Mum’s saying’s drowned out by the gravy roar of the bus pulling away, revealing a pub called The Fox and Hounds. The sign shows three beagles cornering a fox. They’re about to pounce and rip it apart.

The character, the first-person narrator whose name, we later learn, is Nathan, knows some things we readers don’t. He knows what city they’re in; he knows approximately where they’ve just arrived and what they’re going to be doing; he knows how he feels about this errand they’re on; he knows his mother and his relationship with her.

But these lines from the book give us the proverbial tip of the iceberg for all of those things. They don’t fully reveal any of that information, thereby leaving the reader to ask questions about the very things Nathan already knows. What are they doing? Where are they? Why is he already reading predatory intent into pub signs?

That’s how mystery draws us in. We read on because we want to catch up with what the characters in the story already know.

Robert McKee points out that mystery, which you could call a writer technique for engaging the reader, creates curiosity.

Suspense

Suspense occurs when the audience knows as much as the characters. They don’t know what’s going to happen and neither do we. We thus co-experience their unknowingness and read on not only out of curiosity but also concern. But suspense doesn’t have to involve axe murderers around the corner or precarious rope bridges suspended above raging rivers carved into deep canyons. Concern is just a matter of investing in outcomes that neither we nor the character yet know.

Here’s a later excerpt from Slade House, just 9 pages into the novel, after Nathan and his mum have walked through an alley and entered a gate that opens to a beautiful garden and house:

“Mrs. Bishop and son, I presume,” says an invisible boy. Mum jumps, a bit like me with the happy dog. “Up here,” says the voice. Mum and me look up. Sitting on the wall, about fifteen feet up I’d say, is a boy who looks my age. He’s got wavy hair, pouty lips, milky skin, blue jeans, pumps but no socks and a white T-shirt. Not an inch of tweed, and no bow tie. Mum never said anything about other boys at Lady Grayer’s musical soirée. Other boys mean questions have to get settled. Who’s coolest? Who’s hardest? Who’s brainiest? Normal boys care about this stuff and kids like Gaz Ingram fight about it. Mum’s saying, “Yes, hello, I’m Mrs. Bishop and this is Nathan—look, that wall’s jolly high, you know. Don’t you think you ought to come down?”

“Good to meet you, Nathan,” says the boy.

“Why?” I ask the soles of the boy’s pumps.

Nathan now knows no more than we do about this boy and how the interaction with him will go. So we’ve departed from mystery. But because we are equally in the dark as Nathan, we’ve encountered a suspense situation. At this point, we may not feel any threat exactly. But as I said, concern doesn’t have to be about danger. Concern arises from anticipating a change for a character with whom we empathize.

Dramatic Irony

The final situation is the dramatic irony situation. In dramatic irony, we know more than the character. When Romeo finds Juliet dead, we know that she’s not really dead and we watch in horror as he drinks poison to “join her” in death. In dramatic irony, it’s not curiosity that we feel. It’s concern alone.

Now, it’s worth pointing out that these three situations are not always entirely distinct and separate. We know Juliet’s not dead, so there’s dramatic irony surrounding Romeo’s reaction, but we’re still surprised by his offing himself. Then Juliet wakes up. We know more than she does about what happened while she was unconscious, but we don’t know how she’ll react. Dramatic irony quickly becomes suspense in many cases.

In Slade House, that boy Nathan met—his name’s Jonah—asks him to play “fox and hounds.” Jonah explains that it’s a race around the house. “You stay here,” he tells Nathan. “I’ll go round the back. Once we start, run anti-clockwise—up this way.” Nathan waits for the go-ahead from Jonah, and as he’s waiting, he sees a woman in a window: “her forehead’s furrowed and her mouth’s slowly opening and closing like a goldfish. Like she’s repeating the same word over and over and over. I can’t hear what she’s saying because the window’s shut. . . . She could be saying, ‘No, no, no’; or ‘Go, go, go’; or it might be ‘Oh, oh, oh.’”

We’re not exactly in a dramatic irony situation there, but we might remember the opening, in which Nathan observed the hounds about to pounce on and rip apart the fox. That, combined with this ominous woman and with the fact that Nathan is about to play “fox and hounds” with this strange boy—it all adds up to our feeling uneasier than Nathan about what’s happening here. So there’s a mixture of suspense and dramatic irony.

I’m realizing just now that my analysis of all this sure is making it seem like Slade House wasn’t the first book I pulled off the shelf, but I swear it was. It’s the first and only book I’ve looked at today, in fact. It goes to show that you can find these situations in any good story.

Learn How to

Mystery, suspense, and dramatic irony are the tools writers use to create tension and thus to pull readers into the story. Knowing how to create tension ranks up there as one of the most important skills for anyone writing stories.

Learn more in my Foundations of Tension class, which goes into much more depth with these three techniques, exposing the ideal situations for all three, analyzing their employment by great writers, and helping you learn how to execute each. You’ll get the chance to put the techniques to work and get feedback from the instructor and other students.

As long as you have tension on every page, you can get away with an otherwise pretty imperfect story. This is one skill it’s worth investing some time and energy on.

Here’s what Ben Reese, recent graduate of the Iowa Writer’s Workshop, has to say about working with me: “Having spent the last 7 years of my life inside college writing courses and continued studies programs, I can confidently say Tim Storm is one of the most memorable and informative teachers I have come across. He teaches the art of storytelling from a unique perspective that is intuitive and engaging. If you ever have the chance to take a class taught by Tim Storm, take it.”

SaveSave

SaveSave

SaveSave

SaveSave

SaveSave

SaveSave

SaveSave

SaveSave

SaveSave

SaveSave

SaveSave

8 Responses

What happens to Nathan?

Oh, it’s not looking good for Nathan, is it?