This is not a how-to article. You’ll find no prescriptions here. This is just an investigation of some of the artistic choices you might consider in creating a dual-POV story.

So often, when I get how-to questions, my answer is “it depends.” It’s a frustrating answer, to be sure, but it’s the truth. Very little in the world of storycraft comes down to a simple prescription. Should you outline your story? Not necessarily. Showing is always better than telling, right? Nope. Avoid filter words? Sometimes, yeah, but not in all cases. Don’t begin with exposition? A whole lot of the most critically acclaimed books in the past few years did.

And so it goes with dual-POV. In my Writing Craft Club, I recently got several great questions about writing dual-POV stories, and afterwards, I did somewhat of a deep dive on my go-to response of “it depends.” So this article lays out at least a few of the things it depends on. And yes, a lot of these considerations apply to books with more than two POVs (I not discussing omniscient here, but I do have a class on omniscient POV).

Convergence/Divergence

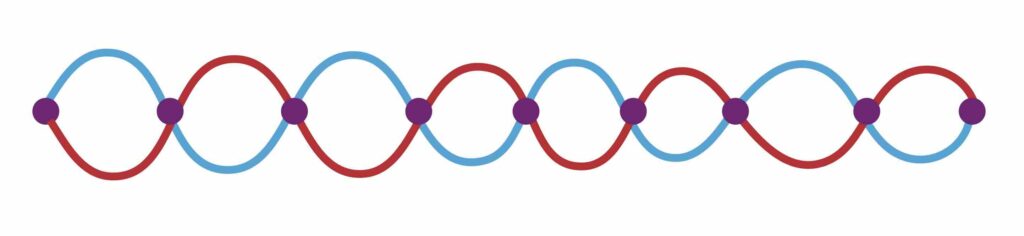

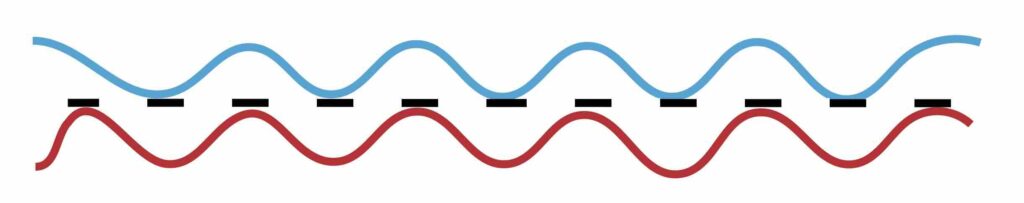

Woven

Let’s first consider that in any novel with two or more POVs, the POV characters may be physically together or separate at various points throughout the story. Most commonly, perhaps, the kind of dual-POV story you’ll see will have the characters interacting a fair amount, but will also allow us to see them apart. A book like The Time Traveler’s Wife, for instance. You could say that the shape of that looks more or less like the image below, with variations in the frequency of comings-together and duration of interactions, of course.

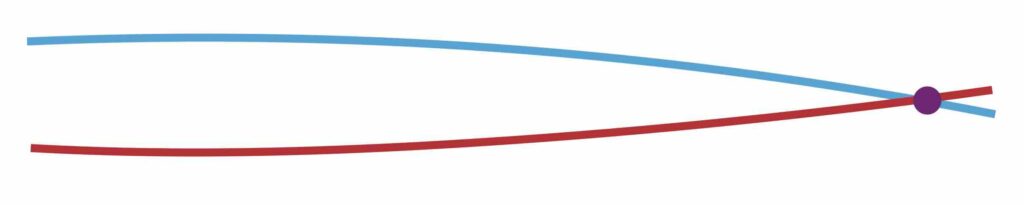

Convergence

But that is not the only shape. A story might begin with the characters having separate, parallel plots until near the end where they finally converge. Cloud Cuckoo Land is a multiple-POV story, but it utilizes this convergence shape in the 15th-century Constantinople parts of the book, depicting POV characters Anna and Omeir separately until late in their narratives.

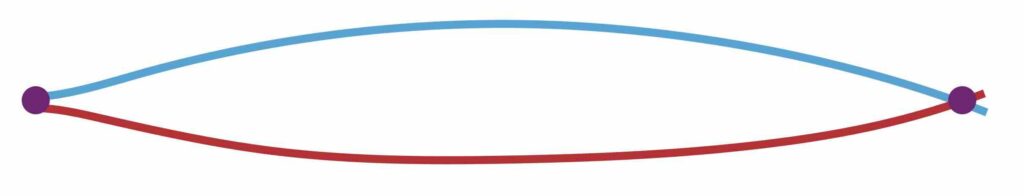

Bookend

You might also have characters together at the start and end but divergent throughout the bulk of the story. An example: Twin scientists Ava and Mira invent a time machine. During the first test, Ava is accidentally sent 20 years into the future. The two work to rectify the problem separately and only come back together late in the story.

Parallel

Some plots might never really bring the characters together at all. You may have heard these referred to as parallel plots. Characters in completely separate timelines, for instance, might be parallel plot stories. A woman plants a tree in Hiroshima, 1945; her grandson, an architect builds a memorial on the same site in 2045. The tree’s growth bridges their stories; they never meet. Parallel plots tend to be pretty “literary” and are perhaps more often seen in a multiple-viewpoint story. In Cloud Cuckoo Land, for instance, Anna’s story and Zeno’s are parallel plots. They never interact, but are linked via the folio.

It’s possible, though, to have a parallel plot that isn’t just thematic, but actually has the two characters interacting indirectly via a main plot thread. Character A may touch upon the main plot stuff, but not when Character B does. And then Character B may touch upon the main plot apart from Character A. They may never interact, but they’re still influencing the main thread of the story. You’ve likely seen this sort of interaction between a protagonist and an antagonist, especially if the antagonist is never actually caught.

None of the above is the “correct” way to do dual POV. You have many options for when or if you have your two characters converge. And you also have a few options in terms of how the characters share the narrative arc, which I’ll discuss next.

Structural Alignment

This question about structural alignment is one I get frequently. Should the two characters share an inciting incident? What about other big points in the story? The midpoint? The climax? Do we want a cohesive narrative arc as the spine of the story, and should the two characters adhere to that?

Again, it depends.

You have options, and I’m roughly breaking them down into three types: aligned, staggered, and linked.

Aligned

Aligned structure means that characters do share major plot points. If the story shape is one in which the characters begin together, diverge, and then come back together later, then an aligned inciting incident is likely. I’d guess that the majority of dual POV stories bring the characters together in the climax. But two characters on a quest together may indeed share almost every major plot point of the story.

There is definitely no requirement to align the characters structurally, however. Some dual-POV stories essentially feel like two stories. Some feel like one story explored from two different angles. Neither approach is more “correct” than the other.

Staggered

Another option is to stagger the structure. Staggered structuring means that plot points for each character happen at different times and with no causality between them. In a romance, Character A’s inciting incident might be losing their job (forcing them to move), while Character B’s is losing a roommate and thus needing to find a new one. It’s likely that the story won’t remain staggered throughout; the characters may come together for at least the climax. But it’s worth keeping in mind that staggering a plot point is an option.

Linked

Linked structuring has separate timing but with causality. In Gone Girl, Amy’s disappearance (Nick’s inciting incident) and Amy’s decision to fake her death (her own inciting incident) are causally linked but distinct.

Over the course of your story, you may vary the alignment. Characters may begin aligned, but then be linked at the plot point that signals a movement into Act 2 and then perhaps move toward fully divergent/staggered midpoints, etc.

The point here is that there is no mandate to align your characters’ plot points all the time. Nor do you even need causality between the two POVs.

Now, there’s usually some other form of cohesion between the POVs if there’s no causality. We’ll touch upon that next.

What’s Shared?

If you’re writing a dual POV story, there’s a reason you’re doing so. Both characters are essential to the narrative in some way. The question is how are they connected? What do they share?

Desire

Probably the most common overlap between the characters is desire (aka objective, aka goal, etc.). Shared desire can put characters in opposition (if they’re competing for an objective) or in alliance (if they’re working together toward a common goal). And of course, they don’t need to remain pigeonholed into one category or the other. They can bounce back and forth between opposition and alliance.

Opposition

A shared antagonist (or force of opposition) can sometimes create the point of confluence between the two characters. Two children of an abusive father. Two passengers aboard a derailed train. Two rebels fighting an oppressive regime.

A subset of the shared antagonist may be a shared event scenario. You take an impactful event like a tsunami or a school shooting and you show us how two people react to that event. The characters may never actually interact.

Theme

Indeed, sometimes, you need not bring the characters together physically at all. Instead, they can share theme. This probably happens more commonly in multiple viewpoint books rather than dual POV, because if you’re going to explore theme, it’s probably worth exploring more than just two facets (think Cloud Atlas or The Overstory). But let’s say you had one POV from the perspective of a firefighter who failed to save her team during a wildfire and the other POV from a journalist who was the only member of her crew to survive a flood. They’re essentially separate stories, but the themes and situations might mirror one another.

Knowledge

Shared knowledge (or asymmetrical knowledge) can be another reason for dual POV. Both characters know the same secret, truth, or piece of information—or one knows something the other doesn’t. Gone Girl does a lot with the nature of knowledge between the two main characters. But for a purer asymmetry, consider The Wife Between Us: Vanessa knows her ex-husband is abusive; Nellie doesn’t. Psychological thriller does a lot with this shared-knowledge linkage.

Object

And finally, a shared artifact/object might be a big part of how the characters come together. The Overstory is a multiple-viewpoint story that centers around trees. The Cartographers revolves around a map. Cloud Cuckoo Land unites various plots via a rare manuscript.

A big lesson to come out of the above is that the linkage between the two plots in the story can be based in causality or in thematic echoes. There’s perhaps a cost for linking via thematic echoes: you’ll essentially be presenting two distinct stories, and so you’ll have to create an engaging narrative in both, asking readers to draw thematic connections but not giving them the more-expected causal connections. It’s an option that tends to be more “literary,” but it can work.

A Big List of Potential Approaches

In short, if you’re writing dual POV, then you’ll have some decisions to make about how the characters come together, when they come together, and what exactly they share. If all of the above is too theoretical for you, though, it may help just to examine how other dual-POV stories have handled the design of the narrative and the relationship between the two POVs. So I’m supplying a list of approaches you might find in a wide array of genres.

Feel free to use whatever approach (or combination of approaches) may suit your ideas. (This may also be a good place to dig around for comps.) And a disclaimer: a few of these are technically *multiple viewpoint.

1. Structural Tropes

- 50/50 Alternating Chapters – Strict back-and-forth (e.g., Will Grayson, Will Grayson by John Green and David Levitahn, The Love Hypothesis by Ali Hazelwood).

- Asymmetric Timeframes – One POV in the past, one in the present (e.g., The Seven Husbands of Evelyn Hugo by Taylor Jenkins Reid).

- Converging Timelines – Start apart, slowly intersect (e.g., 1Q84 by Haruki Murakami).

- Dramatic Irony Engine – One POV knows a secret the other doesn’t (e.g., The Silent Patient by Alex Michaelides).

2. Character Dynamics (Relationship Tropes)

Romance-Centric

- Enemies to Lovers – Each POV reveals their grudging attraction (e.g., The Worst Best Man by Mia Sosa).

- Fake Dating – One POV is faking it, the other might not be (e.g., To Love Jason Thorn by Ella Maise).

- Miscommunication Angst – Both POVs misinterpret each other’s actions (e.g., The Heart Principle by Helen Hoang).

- Second-Chance Romance – One POV dwells on the past, the other resists (e.g., Every Summer After by Carley Fortune).

- Forced Proximity – Trapped together (e.g., The Darkness Outside Us by Eliot Schrefer).

Conflict-Driven

- Opponents to Allies – Like Enemies to Lovers but not driven by romance (e.g., Legend by Marie Lu, This Is How You Lose the Time War by Amal El-Mohtar & Max Gladstone)

- Foil Characters – Contrasting worldviews or attitudes, often in indirect conflict (We Are Not Like Them by Christine Pride & Jo Piazza).

- Betrayer/Betrayed – One POV hides a secret (e.g., Gone Girl by Gillian Flynn).

3. Thematic/Emotional Tropes

- Mirrored Wounds – Both POVs grapple with either a shared or parallel trauma (e.g., The Last House on Needless Street by Catriona Ward).

- Opposite Arcs – One grows darker while the other heals (e.g., The Distance Between Us by Maggie O’Farrell).

- Call-and-Response – One POV character’s emotional state directly influences or contrasts with the other’s (e.g., Today Tonight Tomorrow by Rachel Lynn Solomon, Normal People by Sally Rooney).

4. Genre-Specific Tropes

Fantasy/Sci-Fi

- Chosen One + Skeptic – One believes in destiny, the other resists (e.g., The Bone Shard Daughter by Andrea Stewart*).

- Captor/Captive – Power imbalance with shifting loyalty (e.g., The Jasmine Throne by Tasha Suri).

- Mind Link – Telepathy or shared visions (e.g., The Darkness Outside Us by Eliot Schrefer).

Thriller/Mystery

- Unreliable Narrator Duo – Both POVs lie to the reader (e.g., The Wife Between Us by Greer Hendricks & Sarah Pekkanen).

- Investigator/Suspect – Dual perspectives on a crime (e.g., Behind Her Eyes by Sarah Pinborough).

YA Contemporary

- Sunshine/Grump – Tonal contrast (e.g., Better Than the Movies by Lynn Painter).

- Race Against Time – Dual POVs in a countdown (e.g., The Sun Is Also a Star by Nicola Yoon*).

5. Narrative Device Tropes

- Letters/Texts Only – Epistolary dual POV (e.g., This Is How You Lose the Time War by Amal El-Mohtar & Max Gladstone).

- Diary vs. Reality – One POV is written, one is lived (e.g., The Silent Patient by Alex Michaelides).

- Afterlife/Present Life – One POV is dead or otherwise supernatural (e.g., The Invisible Life of Addie LaRue by V.E. Schwab, A Certain Slant of Light by Laura Whitcomb).

Okay! Hope that was helpful to you. See also David Long’s list of “Polyvocal” stories for some more examples of dual POV.