Things need to happen in a story, but not all action is compelling. Here, we discuss three requirements for action in your stories:

- Movement (the action needs to change characters)

- Incremental progress (we need to see some progress against goals)

- Success/Failure (we need to know the larger goal and stakes)

Now, I’m using a questionable analogy to football for this lesson; you can see it in the video below if you’re a visual learner. Otherwise, the text below should do the trick. Either way, though, be sure to check out the flowchart at the end of the post.

Stories Require Action

Let’s talk action.

We writers enjoy language. We enjoy evoking an experience with our words. We enjoy digging into character tics and motivations and flaws. We enjoy transporting readers to new or fantastical or impossible places.

Those things can be part of a story, but they are not in and of themselves a story.

Stuff has to happen in a story.

I’ve worked with a fair number of writers who either begin their novels with nothing happening or interrupt a story to deliver pages and pages of exposition or description.

Readers come to stories to see characters do things, not just be things. Existence is not a story.

[For more on what constitutes a story, see my free course on The Five Key Elements of Story.]

Action vs. Movement

Okay, then. It’s easy enough to understand that action is necessary in a story. But there’s a next step to this whole thing: not all action is movement.

Movement?

Yeah, movement. Indulge me for a moment as I attempt a football analogy. I’m not really a[n American] football fan, but everyone else in my home state is, so I have some familiarity with the sport. And here’s one of the things I understand:

You can run dozens of yards with the ball but still not progress forward on the field.

Let’s say the red team has possession. What they’re trying to do ultimately is get the ball into the end zone, but they can settle for a first down. That is, they want to get the ball past a moveable marker that some dude on the sidelines holds ten yards further downfield from wherever the player landed on the previous successful passing of the first-down marker.

Yeah, don’t overthink this yet. We’re not yet at the really important part, which is this: our red player might run forward a little, then backtrack and cross the field and then make some modest forward progress only to effectively end up exactly where he began. Lots of moving, no progress.

Similarly, in your story, you might have a character who technically does things—leaves home, drives to a gas station, fills up, cleans windshields, drives to work, punches in, etc. But unless the action is moving toward or away from some objective, it’s likely not going to be compelling for readers. Just as a football game full of failed attempts at first downs is boring.

Some small change needs to come from the action.

Incremental Progress

This first-down thing is one of the weirdest parts of American football. No other sport has such built-in milestones as players move toward an objective. But the first downs in football are precisely what make it a good analagy for storytelling.

A football game is exciting when we see a team struggle for first downs and progress up the field toward the endzone. It actually adds to the suspense when we see incremental progress.

The red team gets to this first-down marker after two attempts, then throws and gets well beyond the new first-down marker, then takes three attempts to get beyond the next first down, etc.

For the writer, first downs are where we see the goals shift a bit. The end goal may not shift, but the immediate goal does.

The protagonist gets called to her sister’s to help with something. The goal is to fing out what. The sister is pregnant. The goal is to help deliver the baby. The baby is a literal monster. The goal is to keep everyone safe from it. The protagonist fights with the sister about how to deal with the baby. The goal is to convince her to contain it.

In a story, the goals shift a bit within scenes, from one scene to the next, and from one act to the next. And that incremental progress is compelling to watch.

The End Zone

Remember that all progress is in relation to the end zones. In football, one end zone means the team scores points. But if a team is backed up into their own endzone, they’ll lose points and lose possession.

Thus, all progress is measured clearly by how much a team progresses toward one end zone or the other—toward success or failure.

In stories, readers need to be pretty much constantly aware of the “end zones.” What is the character’s ultimate goal? What does success look like?

And what does the character have to lose? What does failure look like? A compelling story has clear end zones and even if we see incremental progress, that progress means something because 1) the character sometimes fails, and 2) we’re constanly aware of how bad it could get.

The Flow

Did that football analogy do anything for you? I won’t be offended if it didn’t because I’m not a football fan myself, but as Wayne Gretzky once said, “100% of the analogies you don’t create don’t help writers craft better stories.” At least I think it was Wayne Gretzky. I’m not a hockey fan either.

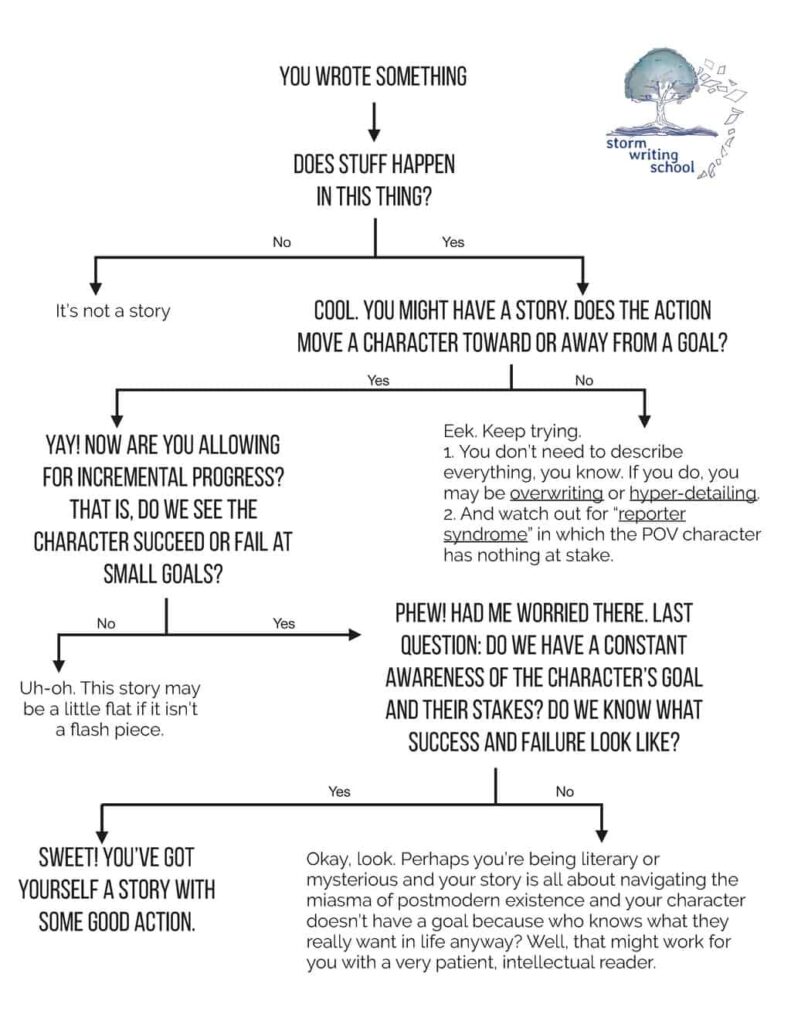

But here, let me do something for you: a flowchart!

Links in the flowchart:

3 Responses

Thanks for including a link to my article!