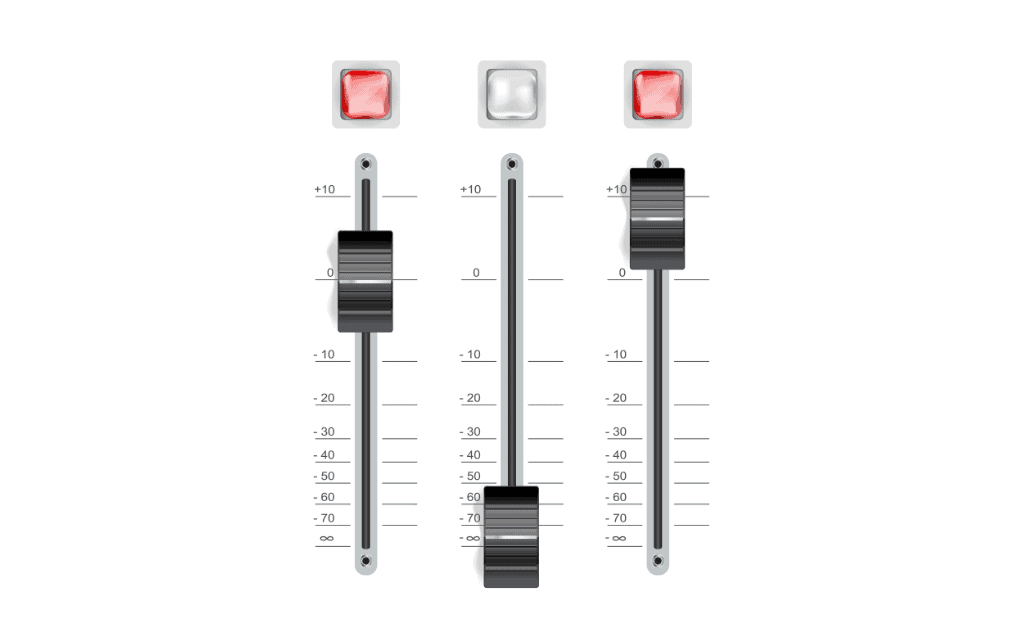

This week, I’m exploring the fascinating concept of “three-pronged character development,” which comes from writer Brandon Sanderson on the Writing Excuses podcast. Sanderson posits that there are three quotients that you can “slide up and down to create an engaging character” as a sort of character mixing board.

The Three Prongs

The first is sympathy, which is about “how sympathetic or relatable [the character is], how nice they are.”

The second is competence. Characters must have either the knowledge or the skill to effect change within the story.

The third is proactivity. “I like characters who do something,” Sanderson says, “who ‘protag.’”

You can slide the mixers on the mixing board for these various traits to create different kinds of characters.

Examples

For instance, Indiana Jones is pretty high on the sympathy and proactivity scales, but relatively low on competence:

Harry Potter is high on sympathy (at least in the first few books) and pretty low on competence and proactivity. Same with The Dude in The Big Lebowski:

Slide sympathy way down, though, and you might still have an engaging character if they’re high on competenece and proactivity. Most villains fall into this category. As do anti-heros, like Kvothe in Patrick Rothfuss’s The Name of the Wind:

Can you have a character be at full capacity for all three? Sure, but then they’re likely a “Mary Sue” like Superman and most James Bonds. So you may risk making them unengaging. They’re essentially without flaws, so you have to ramp up the external conflict very high.

Sliding Scales

Now, if you’re familiar with the above stories, you’re on to the fact that these scales slide up and down over the course of the plot. Harry Potter gets slightly more competent by the end of the first book, and he gets a lot more proactive. In fact, he really comes to embody the Gryffindors’ principal trait: do what is necessary.

Indeed, most characters change over the course of the story, so each situation in the story will likely alter our impression of the character just a bit. As such, it’s tempting to add a plot slider here, to show that as danger intensifies, our engagment in the character may also intensify. But Sanderson argues we should keep that separate. This three-pronged thing is about the character.

A Fourth Prong?

There’s a compelling case to be made, however, that we could add a fourth slider for power. For example, Tyrion Lannister from Game of Thrones is pretty high on competence, but he can’t do much with that competence because he lacks power at many points throughout the story.

For Troubleshooting

Sanderson is quick to point out that this paradigm has some limits for character creation. He mostly uses it as a troubleshooting tool. If he’s finding that a character of his is not quite working, he thinks about how he might tweak one of the prongs (not all).

Problems with the Paradigm

I find this paradigm’s base concept to be something worth considering in the editing process. But its utility falls away if you dig too deep into it.

The sympathy meter seems to throw a lot of traits into the same pot. A relateable character is not necessarily one you’d admire. An admirable character is not necessarily nice. A nice character is not necessarily relateable.

And if you try to keep track of these various quotients over the course of a story, you might find it a little overwhelming. Peter Quill from Guardians of the Galaxy is a good example. He’s pretty selfish, he’s often incompetent, and his proactivity tends toward more self-serving things. And yet, all three of those traits vary so much. He has moments in which he sacrifices his needs and desires for others. He’s actually quite competent in a fight. And once he’s committed to something, he’s mostly all in.

It’s not that Quill disproves the slider paradigm. It’s just that he shows how much sliding up and down might occur over a story.

The Takeaway

You’ll get the most out of the paradigm if you keep its very astute root concept in mind: 1) take the three or four reasons you find literary characters engaging and 2) consider how those categories of engagement manifest in different proportions within different characters. A few lessons:

- Characters can and should be dynamic within each category

- Characters that fall short within at least one of the categories tend to be more interesting

- So you don’t need to (and probably shouldn’t) have characters high up on all the scales

- If you’re troubleshooting a dud of a character, consider upping one category only

My previous posts about what makes protagonists engaging and how you can create standout characters add some crucial concepts to the discussion of how to make characters engaging. Look to those if you’re drafting or troubleshooting characters, and consider the sliding scales if they help.

3 Responses

I use a similar system for minor characters but one that uses any three traits which can be positive, negative or neutral depending on the personality type you want to create, as show below.

Personality Types and their Traits:

(1) Very Good = 2 Positives + 1 Neutral

(2) Good = 2 Positives + 1 Negative

(3) Normal = 1 Positive + 1 Neutral + 1 Negative

(4) Bad = 2 Negative + 1 Positive

(5) Very Bad = 2 Negative + 1 Neutral

A neutral trait is one that can be either positive or negative depending on the circumstances and the other two traits that go with it.

Thanks, Grant! That system makes a lot of sense!