The extent to which you plan in advance of writing a story is often framed as the “plotter vs. pantser” debate. The plotters advocate outlining and preparing before beginning the story, claiming that doing so will save a lot of time in the long run. The pantsers—so named because they write “by the seat of their pants,” advocate discovering the story as they write. E.L. Doctorow famously articulated what is more or less the attitude of pantsing: “Writing is like driving a car at night. You can only see as far as your headlights, but you can make the whole trip that way.”

Stephen King is a little more severe with his pro-pantsing philosophy: “Outlines are the last resource of bad fiction writers who wish to God they were writing masters’ theses.”

Ouch.

I mistrust blanket statements about writing process, so I’m not here to tell you that one way is superior to the other. However, I can explain some of the rationale for discovery writers, if only to validate your decision not to outline.*

It’s How Creativity Works

The creative process sometimes necessitates just diving into the art in order to figure out what the art is going to be.

Listening

It’s a question of listening, “constantly asking questions of the story as you move forward into the narrative and then letting the answers inform the direction you take as you write it.” So says Steven James.

And though we could argue that there are outlining methods that incorporate listening to a certain extent (Robert Olen Butler’s dreamstorming, for instance), most of us aren’t Beethoven; we can’t hear the music unless we’re playing it.

Creativity is an iterative process, we could argue, and it relies on a circular interaction between what you’ve created and what you have yet to create.

Exploring

“Discovery writing,” as it’s sometimes called, allows for more exploration than outlining does. Because the course of the story is not predetermined, you have that freedom to test out the new directions you’ve discovered through listening.

Steven James advocates following rabbit trails:

Forget all that rubbish you’ve heard about staying on track and not following rabbit trails. Yes, of course you should follow them. It’s inherent to the creative process. What you at first thought was just a rabbit trail leading nowhere in particular might take you to a breathtaking overlook that far eclipses everything you previously had in mind for your story. You’ll always brainstorm more scenes and write more words than you can use. This isn’t wasted effort; it’s part of the process. Every idea is a doorway to the next.

So one argument is that discovery writing is simply the way creativity works. You remain receptive to the story taking new directions, and you allow yourself to explore those new directions.

You Get Better Movement and Believability

Pre-plotted stories can sometimes feel a little stilted. As William Blundell says, “Tortured transitions are the mark of an outlined story.”

Plotters sometimes rush their characters through to pre-planned plot events without earning their characters’ arrival at those events.

Discovery writers thus make the case that their method leads to a more believable sequence, which in turn can lead to more authentic-seeming characters.

As Daniel Silvermint points out, “Pantsers have an easier time writing realistic characters because they generate the plot by asking themselves what this fully-realized person would do or think next in the dramatic situation the writer has dropped them in.”

Plotters, on the other hand, might suffer the inverse: “The impetus to move the story to the next plot point is so strong that it can end up overriding the believability of the character’s choice at that moment of the story” (James).

You Have More Access to Context

Pantsers may be better equipped to create believable character action for one simple reason, really: they have greater access to the immediate context of the story.

They can figure out where the story should go based on where it has gone. So can plotters, you might argue, but plotters are generally dealing with larger chunks of the story, not the minutiae, not the twists and turns and quick, consequential decisions that occur within scenes.

Any fiction writer knows that it only takes a very small thing within a scene to radically change the direction of a character’s arc and action.

And discovery writers have access to that small-but-consequential context.

Discovery writing is “an interplay of responsiveness to the movement and context of the unfolding story. It only comes from a constant awareness of where the story has been, where it might go, and what readers want and expect” (James).

Surprise Yourself; Surprise the Reader

I’ve seen it in many author interviews: when asked whether they plot a story ahead of time, the discovery writers among them say something like, “If I’m not surprised, the readers won’t be.” And indeed, if you’ve ever had that experience of being in the midst of drafting a scene and watching it take a direction you didn’t anticipate, you know it’s pretty exhilarating.

I can understand why pantsers would push for others to experience that surprise.

Can you plan out twists and surprises ahead of time? Probably. But it’s likely less fun. And pantsers would argue that pre-planned surprises are less authentic.

Practice Uncertainty, an Imperative of Art

And this brings us to one of the more interesting concepts having to do with discovery writing: when you pants your way through a story, you have to live in uncertainty. And as David Bayles and Ted Orland point out in Art and Fear, “Uncertainty is the essential, inevitable and all-pervasive companion to your desire to make art. And tolerance for uncertainty is the prerequisite to succeeding.”

Living with such uncertainty might seem scary; I’m sure that’s part of why so many writers think they need to outline. But such uncertainty can actually be freeing. When you write without an outline, you’re not writing without a safety net. In fact, it may be the opposite. Writing with an outline may make you feel so wedded to the sequence you’ve determined for yourself that revision becomes even more painful. Fall off the outline tightrope, and where do you land?

Whereas if you’ve lived with uncertainty during the entire drafting process, you may be more accepting of change in the revision process, more apt to say to yourself, “This is just a first draft,” to have the attitude of Terry Pratchet: “The first draft is just you telling yourself the story.” Such an attitude might make for more enthusiastic second drafts.

Counter-Arguments?

Now, here’s the thing. If you have counter-arguments for any of the above, wonderful. Write them down and create your own manifesto for approaching story creation.

I have no pro-pantsing agenda here. I just like to explore the question.

I will say, however, that one of the frequent caveats of discovery writing is that it requires that the writer have some knowledge of how stories work. Stephen King has good instincts by now, I imagine. His initial drafts are likely better than a novice’s fourth or fifth draft.

And that pretty much goes for most people who are adamant pantsing proponents. They feel out the story in an organic way because they’re good at feeling out the story.

The irony: you only get good at feeling out the story by doing it.

So pants away. And learn everything you can about how stories work.

One thing is for certain, however: at some point, you have to get analytical and left-brained. You have to look at what you have created and think hard about what it is you’re attempting to do and evaluate whether you’ve done it.

The biggest challenge of pantsing is tying up the loose ends.

*I’m drawing several of the argument from Steven James’s book Story Trumps Structure (the title of which lays out a false dichotomy, in my opinion, between story and structure, which are no more separable than carrot cake and carrots; but the book has some though-provoking tips).

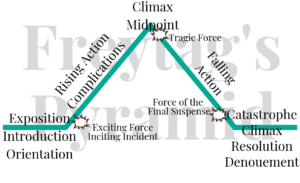

If you prefer to go the outlining route, check out the following:

- A Compendium of Novel Structure Resources

- Novel Structure: An Aggregate Paradigm

- Escalating Complications

- The Two Roles of the Beginning

- Four Common Failures in Story Cause/Effect

- Create a Moving Character Arc

3 Responses

This arrived at the perfect time. I’m a pantser through and through but as I began toying with an idea for a cosy mystery, I figured this genre may require more plotting. I tried. I really did! But it just wasn’t happening. Yesterday I decided to set the MS aside. Now you’ve given me permission (you gave me permission, right?), I’m going to let the mystery write itself. Then, of course, I’ll go back in and follow Tim Storm’s and Michael Hauge’s advice on structure.

Thanks, Tim, for your encouragement!

Yeah! Get back in there and create a huge mess. This is exactly why people need permission to pants. There’s a sense that if you can’t plot it out, it’s not going to be a successful story. But that’s not true.

I’ve just come off of two stories that I mulled over for months, and in that time, I could not figure out where they were going until I just started writing them. Sometimes, that’s how it works.