What is a scene list?

A scene list is just what it sounds like: it’s an ordered list of the scenes within your work-in-progress. For a novel, that list will be pretty big—somewhere between 60 and 130 scenes, most likely. For a short story, you might be somewhere between 5 and 20. But don’t worry too much about the numbers.*

What you’re going for is a one- or two-sentence summary for each scene. You’re looking to capture the essentials of the story. Usually, the scene list is about what happens. Oh, and it’s typically like a synopsis in that it’s written in third-person present tense.

You can format this however you’d like. When I’m working on a short story, I tend to write out a list like this:

Scene 1: MC gathers cash and bikes to Game Stop to get Metal Gear Solid V from cousin.

Scene 2: At home, MC tries to sneak into house but sees father, who wants to say something horrifying or upsetting, but MC tells him he needs to study.

Scene 3: MC goes to room and locks the door and opens up the game to awe at its Afghanistan map.

(The above is the first few scenes of “Playing Metal Gear Solid V: The Phantom Pain” by Jamil Jan Kochai, by the way, which was published in January 2020 in the New Yorker. It’s a wonderful 3000-word story—one of the most successful and earned second-person narratives I’ve ever seen.)

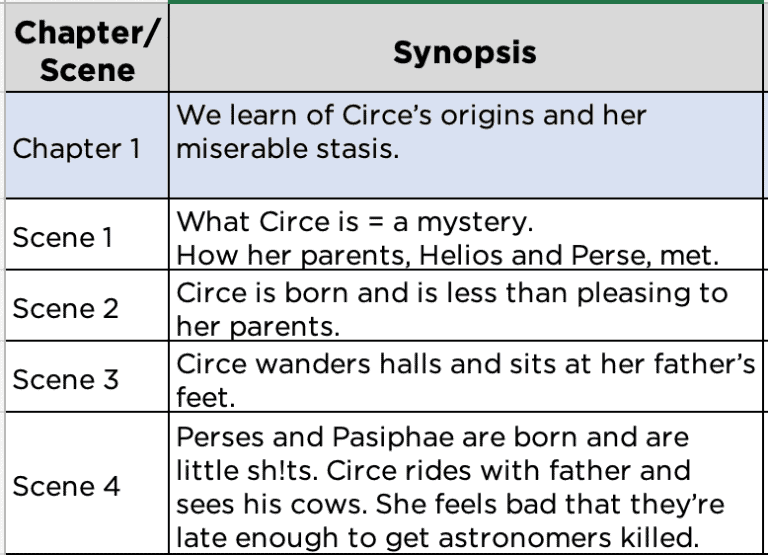

Another popular option for a scene list is to create a spreadsheet document. A spreadsheet gives you the ability to add other columns, where you can take note of important things. More on that later. Below is an example of a spreadsheet scene list from Madeline Miller’s Circe that identifies a quick summary for the chapter and then breaks the chapter down into four scenes.

Why make a scene list?

I create a scene-by-scene summary with pretty much everything I edit. In my critique groups, for each submission I make a bullet-point list of events, which I go over before we discuss the chapter or story up for discussion. When I edit novel manuscripts, I make a simple table in which I summarize scenes within each chapter. When I edit my own work, I often make a scene list akin to what I did above with “Playing Metal Gear Solid.”

The scene list allows me to wrap my head around the big picture of the narrative. When I make a list for novel manuscripts, I rely almost entirely on it for my holistic assessment of the work. I go back and read the scene list I’ve created in order to get a sense for the overall structure of the work and the movement of the main character.

A novel is too large to hold in your head all at once. It’s like trying to see an entire globe; you just can’t see all sides at once. So you sometimes have to rely on a mercator projection, incomplete and limited though it is.

In fact, even a short story can be too much to hold in your head at once. Something that fits in a paragraph or on a single page is much easier to apprehend.

Furthermore, when I make a scene list for my own short stories, I usually come away with a pretty clear notion of what I need to fix. The process of distilling the story into a paragraph’s worth of sentences helps me see the cracks and fissures in the work.

What is a scene?

It’s worth mentioning that for the sake of this exercise, you don’t really need to quibble much with what constitutes a scene. Scenes are native to drama; each time a play changes the cast of characters or the place or the time, the stage maybe goes dark, and a new scene is ushered in. So scene distinctions are very clear.

In prose, things can be a little messier, thanks to things you don’t get in drama—narrative summary, interiority, exposition—so scene delineations are not quite as obvious.

Don’t worry about it. It’s really not important for the sake of what you’re doing here. Go with your gut. A shift in setting, a shift in POV, a shift in the character’s goal—any of these might clue you in to where you’ll want to split one event from another in your list.

What you’re doing with the scene list is just getting a sense of the story’s throughline.

How to use the scene list

You’re revising. So you’re in the revision mindset, which means that you’re looking to cut or alter what doesn’t work; you’re examining whether the change in circumstances and the evolution of the main character feels believable, logical, authentic, and moving.

Figure out your focus for the revision, and then take notes on each scene in accordance with that focus.

If, for instance, you’re looking to trace the character arc, then you would take notes on how each scene affects the main character.

If you’re looking to tighten up your setups and payoffs, you might note what information or foreshadowing is supplied in each scene.

If you’re looking at tension and momentum, you might examine what conflicts and desires and questions are supplying narrative drive to the scene and whether it’s enough narrative drive.

There are lots of things you might examine, but I’d urge a pretty simple list to start with. If you start adding too many columns to your spreadsheet, you’re likely to be overwhelmed. If the scene list isn’t helping you see the whole, you’re defeating the original purpose of the list.

Example: “Playing Metal Gear Solid V: The Phantom Pain”

If you haven’t read this story yet, I’d urge you to do so before you look at the example below because I’m going to spoil the story for you.

What I’ve done here in addition to creating a summary for each scene is to take note of what the scene accomplishes. This story’s strength, and likely one of the greatest challenges the writer faced in creating it, is its thematic coherence around a complex relationship. The main character pushes away his family and Afghan identity but also longs to connect deeply with both. Each scene accomplishes something with respect to that thematic exploration. So I’ve taken note of what each scene does with that focus in mind. Your focus may be different.

| Scene 1: MC gathers cash and bikes to Game Stop to get Metal Gear Solid V from cousin. | Establishes guilt in playing the game. |

| Scene 2: At home, MC tries to sneak into house but sees father, who wants to say something horrifying or upsetting, but MC tells him he needs to study. | Establishes avoidance of father. |

| Scene 3: MC goes to room and locks the door and opens up the game to awe at its Afghanistan map. | Establishes draw to Afghanistan. |

| Scene 4: MC starts playing the game and feels connected to his father as he sheds Soviet blood. Then he explores the open world of the game and makes his way to Logar where he sees his father’s brother, Watak, and panics a little. | Establishes connection to father. |

| Scene 5: MC ignores his sister’s knocking on his door and returns to the game but then sees his father in-game and pauses, eats some kush, and returns to the game, realizing it’s days before Watak’s murder. | Establishes desperation to help save his father and uncle. |

| Scene 6: MC ignores his brothers knocking on his door and fails to tranquilize his father and uncle and ends up alerting all to his presence. | Establishes avoidance of entire family. |

| Scene 7: MC manages to tranquilize his father and then Watak but suffers a machete blow from his grandmother. MC gets away with both of them and heads to the extraction point by horse. | Establishes lengths he’ll go to to save his family. |

| Scene 8: MC’s father comes to the door and gentle says MC’s name, evoking memories of when he was younger in Logar. | Establishes gentleness of father and his sacrifices. |

| Scene 9: MC flees the Russians into the mountains but they kill his horse and the pilot of the extraction aircraft. He takes his father and uncle deep into the cave. | Establishes the impossibility of saving his father and uncle and also the indelible mark they have left on him. |

Add revision notes

Now, if the above were a less capable draft of a story, I might then take note of what changes to consider. Let’s imagine, for instance, an earlier draft of Kochai’s story in which Scene 8 (wherein the father talks gently to the MC outside his bedroom door) has the father arriving angrily at the door and yelling at the main character.

In that case, I may have written something like “Establishes avoidance of father and parallels his desperation to save father.” But both of those things have been established already. And though there’s something to be said for creating a parallel between the MC’s fleeing in the game and his fleeing in real life, it may be better to write the father as someone who doesn’t deserve the avoidance and who does deserve the MC’s desperation to save him.

So I would note something like “Make father sympathetic and gentle. His gentleness evokes earlier childhood for MC?”

And I now would have direction for my revision.

Did Jamil Kochai do the above? No idea. I’m just offering an approach I’ve used often and I’ve seen others get a lot of benefit from. Your mileage may vary, but it’s worth trying out.

Again, there are many things you could examine in your attempt to make your story structurally sound and to give it narrative drive and to make it moving. Give the scene list a try and let me know how it works for you. Questions or comments? Chime in on the comments below or email me: td@stormwritingschool.com.

12 Responses

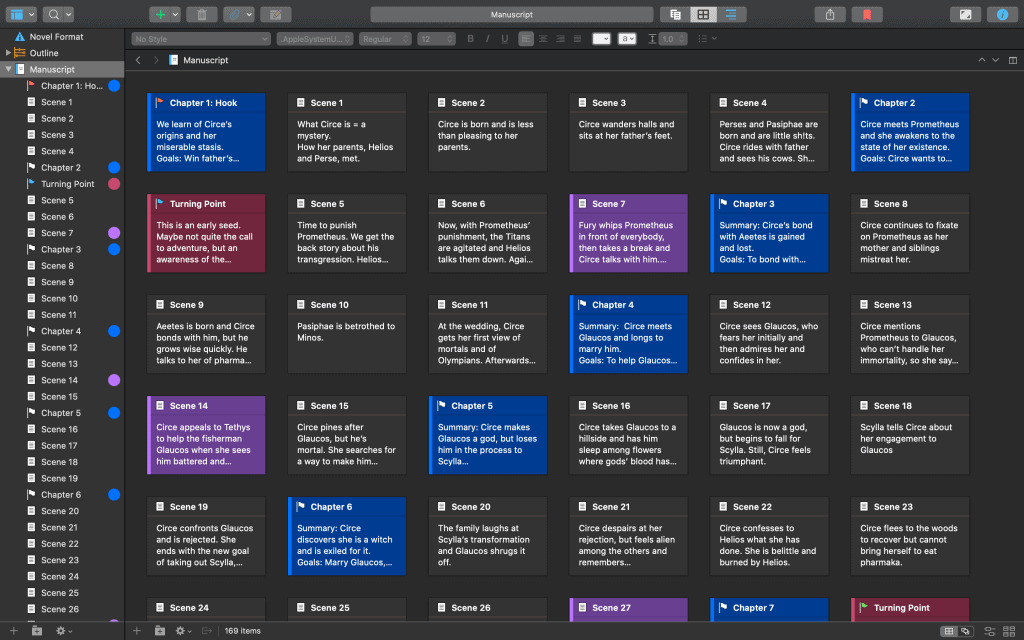

this is really helpful! I want to try this on my next revision. I was wondering what app or program you are using where all the scenes are really close to eachother with the black background? (the main picture)

Hey Hannah, That’s Scrivener. I actually don’t use it much for my scene lists, but it does look cool.

Hi Tim,

This is great! I’m working hard on those pages to get you this summer, and adding a column to track changes for the character might be just what I need, so thanks for the pre-editing help already, haha.

Is your Write by the Lake class the same as last year or building off it/taking a different tack? I don’t know if I’ll be able to make it this year, but I’d definitely be interested to know what you’re teaching just in case!

Thanks!

Abby

Excellent! I’ll be eager to read your work! (And this upcoming WBTL class is the same as last year.)

Great article/post/class. Thanks, Tim. To get a feel for how to do this myself, I wrote my own summary of the first three scenes and compared them to yours, trying to see how it’s done. I noticed when I did it, I left out all the emotional words, like “guilt” in the first scene, “horrifying and upsetting” in the second scene and “awe” in the third scene. I’m having trouble reducing the scene to character arc; feeling a bit frustrated by the process, but fascinated at the same time. I had no idea this is what writers do. No wonder my revisions are so haphazard and time consuming. I just go line by line and wonder if they sound and feel right. I edit by sound and intuition? Emotional resonance? Your method is far more efficient while allowing for artistic decisions and consideration, i.e., is the father a jerk or sympathetic? I have never approached revision in this way.

Please share more info about the summer workshop: Where, when, how much, etc.

Thanks, Tim!

So glad it’s helpful, Polly. In general, my scene summaries are pretty external. Just bits and pieces of character emotion in there insofar as it affects the story moving forward. My scene lists wouldn’t necessarily translate well into a synopsis. But they would give a start. As for the summer retreat, click on that link for more information. It’s a big retreat, with many sections and several wonderful teachers. If you have questions about it, shoot me an email. Thanks!

Hi, Tim.

Would this method work as the format for an outline? I’ve written some short fiction but pantsed it all the way. Just at the thinking stage of something bigger and don’t feel I can wing it like I’ve done with my shorties. Reading this post made me feel like this would work for a planner! Would love your thoughts.

Louise

I definitely think this could work for planning. And in fact, if you have pantsing instincts, I highly recommend Robert Olen Butler’s “dreamstorming,” which he explains in the book From Where You Dream. His process is to meditate on his story every day for a couple months, coming up with scenes and then writing them on index cards, which he later organizes into a more coherent structure.

Thank you! In every other aspect of my personal and business life, I’m a planner. When I write non-fic, I’m a planner. I ache to approach my fiction writing in the same way!

Tim, please explain what you mean (regarding Playing Metal Gear…) when you say: “…one of the most successful and earned second-person narratives I’ve ever seen.”

How do you earn second-person? I have a story I wrote in second person and I don’t know if it works.

Thanks.

Hey Samantha. What I mean is that second person has to feel like it isn’t just a gimmick. I’ve seen several great second-person stories. Lorrie Moore’s “How to Become a Writer” is another great example. The story is framed as a how-to manual and thus its use of the second person feels very warranted. “Playing Metal Gear” emulates the video game player/character approach, wherein what happens to the character in the video game happens to “you” the player.

A writer “earns” second person by having the narrative embody a good reason for its delivery to be in second person.

Great explanation. Thanks. And Samantha, thanks for the question, I was wondering as well.