With the start of the new year, I got my daughter to get back into practicing piano after a six-month hiatus. I printed out a one-page calendar based on Simone Giertz’s Every Day Calendar, and we’ve been bubbling in little diamond checkboxes after each lesson or practice session. I also have a tallying app on my phone that she gets to advance for each new lesson.

I say I got her to get back into the piano habit, but it was contingent upon her willingness. And really, she was the one who jumped on board with the app and the calendar; I just floated those ideas to her.

The thing is, it’s really hard to form new habits if you don’t want to form new habits. So my daughter’s buy-in was step #1 in all this.

But I nudged her a little by putting into practice some lessons I’ve been learning from James Clear’s book Atomic Habits—lessons that have served to aid both my daughter’s piano playing and my own writing practice.

Habit formation is crucial for writers trying to improve their process. And Clear’s book discusses several ways in which we should change our thinking about habit formation. I’d like to outline a few of the key takeaways I’ve encountered as they apply to writer mentality and process, two of the pillars of being a successful writer, which I outline in my Starter Kit.

The Nature of Improvement

I have on rare occasions experienced breakthroughs in the quality of my own writing craft. But a breakthrough is not an isolated event. It is the culmination of prior work.

Put it this way: breakthrough is not a standing long jump; it’s the result of a running jump. As such, breakthroughs rely on the dozens or hundreds of steps that come before them.

James Clear quotes social reformer Jacob Riis: “I go and look at a stonecutter hammering away at his rock, perhaps a hundred times without as much as a crack showing in it. Yet at the hundred and first blow it will split in two, and I know it was not that last blow that did it—but all that had gone before.”

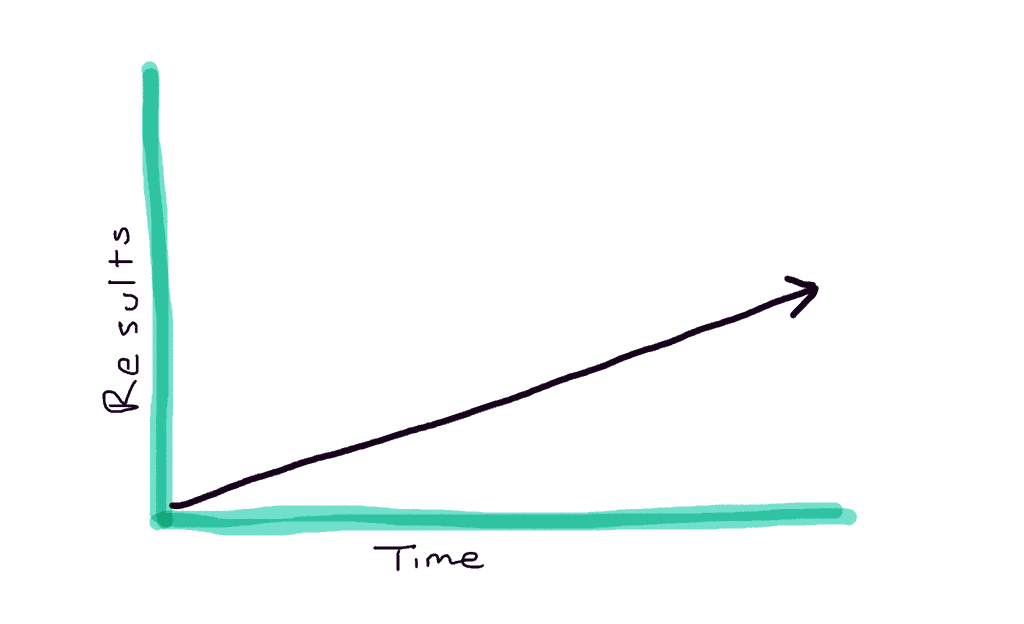

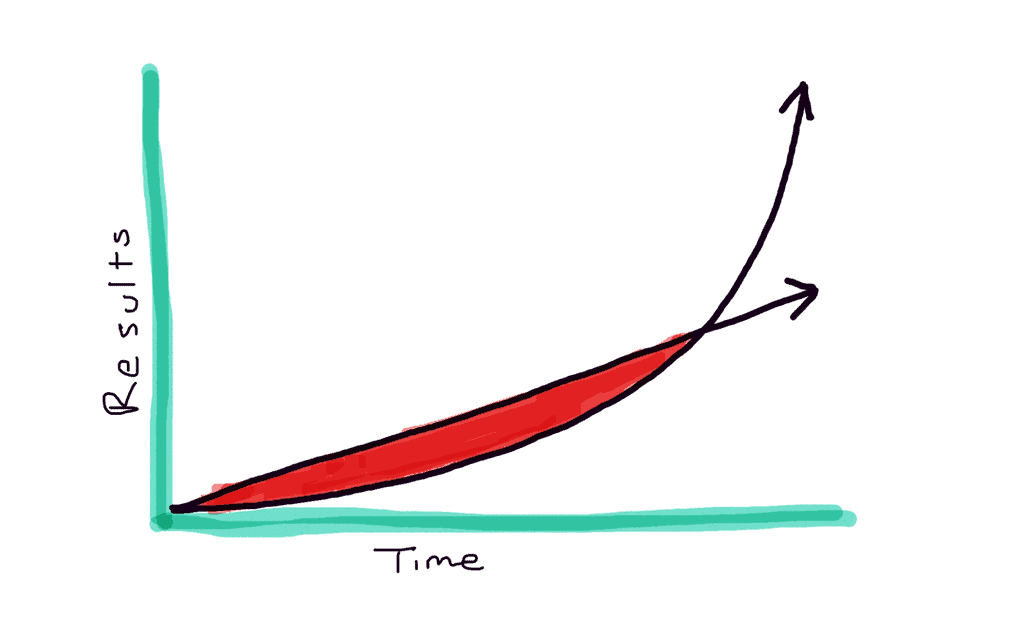

One of the biggest points Clear makes early in his book is that habits result in a compounding effect. Thus, the graph of improvement looks like this:

What’s important to note is that for a long while, it will appear as though the habits are getting you nowhere. But as time goes on, they will start to have an increasingly dramatic effect. Observe a child learning to play piano and you will witness many days of struggle to learn a new song followed by a day in which it all seems to come together and she can’t imagine why she ever thought it was so hard.

When we’re attempting to improve through daily practice, however, we expect the improvement to be linear, like this:

It is not.

And the gap between the two graphs above creates what Clear calls the valley of disappointment, in which people feel discouraged because they don’t see the results they were hoping for.

Focus on Systems, Not Goals

James Clear makes a very important distinction: “Goals are about the results you want to achieve. Systems are about the processes that lead to those results.”

The key to making progress is not through goals. Goals can provide a destination, but it’s the system that is going to determine whether you’ll reach that destination.

In the writing world, some people can get pretty obsessive about goals. Our art might be more quantifiable than other art; we can measure the pages or the word count we produced on any given day. We’re big on setting quotas for ourselves or “winning” certain month-long writing challenges.

But goals can mislead if they get more attention than our systems.

Clear points out a few problems with goals, the first being that winners and losers have the same goals. When the Olympics comes around every couple years, we’re given heartfelt stories about how successful athletes dreamed of being the best in the world. But so did every one of their competitors in the games, not to mention the many other non-Olympians who didn’t make the cut for the games. The goal is not the reason for success.

Furthermore, when we achieve a goal, it’s momentary and maybe even a little overrated. I know so many people who wrote 50,000 words of a novel in month but didn’t do much with it after that month. Clear makes an analogy to cleaning your room. It’s nice if you can accomplish the goal to clean it, but it you don’t change the system of habits that led to its being messy in the first place, it’s going to get messy again quickly. “Fix the inputs,” Clear says, “and the outputs will fix themselves.”

Goals may, indeed, be at odds with long-term progress. Goal-setters can experience a yo-yo effect. (You see this a lot with diet and exercise.) You work hard, you attain the goal, then you take a little break that results in you losing all your momentum and progress. “The purpose of setting goals is to win the game. The purpose of building systems is to continue playing the game.”

Are You a Writer?

I’m not sure if people with other hobbies and passions constantly call to question their own identity as a pursuer of those hobbies and passions. But writers sure do.

We have so much angst about calling ourselves writers.

But if you want to be a writer, the most profound change you can make in your life is to focus on your identity as a writer.

Clear illuminates that “the word identity [derives] from the Latin words essentitas, which means being, and identidem, which means repeatedly. Your identity is literally your ‘repeated beingness.’” (I went down a fun etymology rabbit hole verifying this.)

Thus, being a writer equates to “repeatedly being” a writer. In other words, you’re a writer if you write regularly.

This may all seem obvious, but the key here is that in order to change outcomes, you’re actually best off not focusing on the outcomes. Outcomes are the result of processes and processes are the result of identity.

Clear thus recommends a simple two-step process:

1. Decide the type of person you want to be.

2. Prove it to yourself with small wins.

You want to be a writer; develop writer habits.

The Four Laws

But how do you develop habits?

Clear has four laws for habit formation.

Cue

First, “make it obvious.” The thrust of this first law is that every habit begins with a cue. Cues hardwire human behavior. One of the many stories that circulates among my wife’s family is of her grandmother, who would get into the habit of tossing her unfinished coffee over her shoulder after breakfast each morning whenever they went camping. One day after returning from a summer camping trip, she sat down in the kitchen at home, and after breakfast, she tossed her coffee over her shoulder all over the linoleum and countertops.

You could, of course, write every morning after your morning cup of coffee, establishing a patterned cue for yourself, but you can also just kick off a habit with an “implementation intention.” Name the time and place you’re going to do your activity. For instance: “I’m going to write at 7:00 at my writing desk.”

If you want to write on a regular basis, you likely won’t follow through if you’re vague about your intention. “I’m hoping to get some writing done today” is not going to cut it.

Clear relays a fascinating study in which three groups of people set out to build better exercise habits. The first two groups consisted of the control group and a group that got some motivational speeches. About 36% of each of those groups exercised at least once a week. But in the third group, they stated their intent with the following sentence: “During the next week, I will partake in at least 20 minutes of vigorous exercise on [DAY] at [TIME] in [PLACE].” And 91% of the people in that group exercised.

Motivate

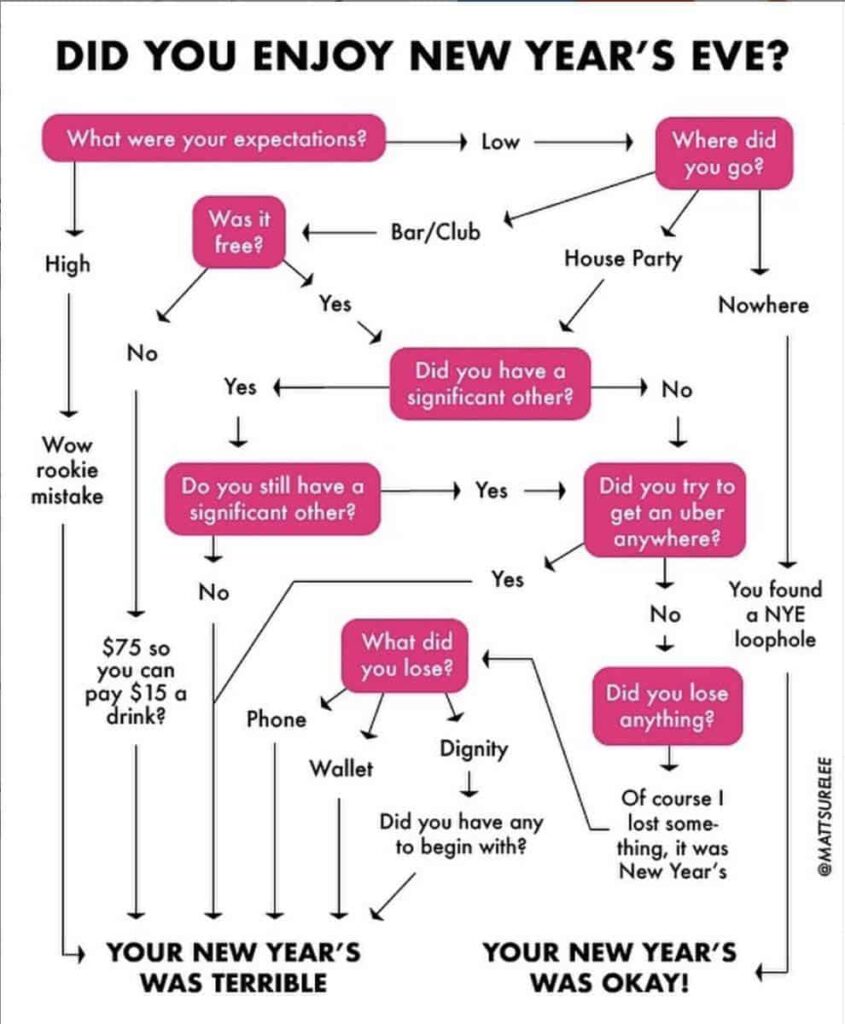

Clear’s second law is “make it attractive.” You have to look forward to the completion of the task. This is a fine point, but an important one: it’s not the reward that spurs action; it’s the anticipation that does. Like, why do people ever go out for New Year’s Eve? (Matt Shirley’s NYE flowchart is spot-on.)

It makes sense, of course, that the anticipation spurs action. Action always precedes a reward, so a reward can’t cause the thing that comes before it.

So how can we up our anticipation and make writing attractive?

Well, for some of us, it’s inherently attractive. We like the process itself; we like escaping into that world we’re building.

In fact, for many of us, we avoid writing because it feels too self-indulgent. If that’s you, ask yourself if you feel better on days when you’ve done some writing. I would argue that we all need exercise and we all need a creative outlet. Both of those activities can get pushed to the side for other duties and more obvious needs. But your wellbeing might actually depend on your finding time to write. Consider that.

For other writers, though, writing is not inherently pleasurable. If you’re experiencing writer’s block or if you’re avoiding a difficult writing problem or if you just have other fun things you’d like to do instead, writing can feel like a chore.

(Personally, I experience both of the above. A first draft is almost always fun for me; revision is almost always somewhat of a chore.)

Clear recommends something he calls “temptation bundling.” It works by “linking an action you want to do with an action you need to do.” And the simplest way to go about it is to make something pleasurable contingent upon your completion of your writing.

“After [HABIT I NEED], I will [HABIT I WANT].”

Let’s say you want to watch a bad TV show like The Witcher (*wink), but you need to write. Well, you can’t watch The Witcher unless you write.

Repetition

The third law is “make it easy,” and this one is all about making the habit seamless and automatic. “If you want to master a habit,” Clear says, “the key is to start with repetition, not perfection.” It would be wonderful if you could do your writing in a cool private office surrounded by bookshelves and a maybe with its own fireplace and a cat. Also, a new computer and a standing desk. Ooh, and a mini fridge with—no, actually, with a personal chef!

You’re likely not going to have that perfect writing setting any time soon, though. So don’t just plan your habit. Do it.

Clear relays a really fascinating story about a photography professor who split his class into two groups. He told one group they would be graded only on the quantity of photos they turned in: 100 would be an A; 90 would be a B, etc.

The other group was to be graded on the quality of their photograph. They only had to turn in one photo all semester, but it had to be nearly perfect to get an A.

At the end of the semester, all of the best photos came from the “quantity” group.

Quantity produces results.

Repetition produces results.

And repetition also makes the habit get increasingly easier to complete.

Immediate Satisfaction

Finally, there’s “make it satisfying.” Here’s the thing about writing. It seems as though the ultimate reward is publication. And sure, that’s what most of us would like to achieve. Some might add “with a wide readership” to their ambitions to be published. But what you need to reinforce your writing habits is immediate reward.

As Clear explains, the human brain is hardwired for an “immediate-return environment” rather than a “delayed-return environment.”

“Similar to other animals on the African savannah, our ancestors spent their days responding to grave threats, securing the next meal, and taking shelter from a storm. It made sense to place a high value on instant gratification. The distant future was less of a concern. And after thousands of generations in an immediate-return environment, our brains evolved to prefer quick payoffs to long-term ones.”

Publishing is not immediate reward. And so publishing will never be adequate to get you to write.

So it will be to your benefit if you can hack your own brain by adding some immediate pleasure to your writing habit. Get it to feel successful.

This can be as simple as marking down your writing session on a calendar or tallying your completion in an app (there are lots that do this: Streaks, Tally, Clicker, Done, Habitify).

Of course, you can also think about the temptation bundling described above. But unlike New Year’s Eve, the reward needs to actually be pleasurable.

Okay, so there you have it. A start to getting you to kick off more successful habits for your writing. Take a look at my Starter Kit to see what else might be holding you back from reaching your writing potential.

This article is part of the Author Toolbox Blog Hop. To continue hopping through other great blogs in the monthly hop or to join, click here and/or search #AuthorToolboxBlogHop on Twitter and Pinterest (here’s the group board).

7 Responses

Tim,

As always, thank you for the thoughtful, engaging, and researched post. I feel like I’ve learned something I can take away (most significantly, the goal vs. systems approach). Thank you for your attention to detail, clear explanations, and motivation.

Best,

Jimmy

I’ve never seen that New Year’s Eve chart before, but I love it!

The photography class is an interesting story. I guess a writing version would be to write a lot of blog posts or short stories to find your voice, rather than a 160,000-word novel that goes nowhere.

I’ve spent some time in the valley of disappointment. I try to vacation there a few times a year. When I’m in nanowrimo mode, I definitely use a reward system for myself. After 250 more words, I’ll get a snack. 250 more and something else. So I give myself a lot of rewards is what I’m saying. P.S. That image totally works in my opinion, as far as us hoppers being able to find your toolbox post.

[…] more on the writing habit, check out Tim Storm’s article How Your Attitude and Approach Toward Habits Can Revitalize Your Writing Practice. This article informed much of the thinking that led me to this post, and he writes more as well […]